Harry Jackson Collection Still Searching for a Home

Written by Caleb Nelson on September 26, 2022

A Western Icon

Harry Jackson, one of the most famous and prolific American artists of the 20th century, is perhaps not as widely known as his friend and counterpart Jackson Pollock, but the scope of Jackson’s legacy is legendary.

The Harry Jackson Institute (HJI) based here in Cody has the largest collection of work by Jackson in the United States.

HJI, however, is still looking for a permanent home for Jackson’s substantial collection of paintings, sketches, studies, and sculptures. Mark Harris, the President of HJI, says Jackson wanted his work to stay in Cody.

Born in Chicago in 1924, Jackson took interest in the American frontier and the Western genre from a young age. As a teenager, he started taking Saturday classes at the Art Institute of Chicago when a teacher secured a scholarship for him after noticing his promise.

In 1937, Jackson saw a photo spread in Life magazine called, “Winter Comes to a Wyoming Ranch,” prompting Jackson to hitchhike to Wyoming. Whether by chance or by fate, Jackson eventually landed in Cody, working as a ranch hand.

The eighteen-year-old Jackson enlisted in the Marines during World War II in 1942. Jackson became a sketch artist for the Fifth Amphibious Corps. He was wounded in the Battle of Tarawa in 1943 and again in Saipan, earning two Purple Hearts. Jackson would carry his injuries with him for the rest of his life in the form of mood disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and epileptic seizures.

Honorably discharged in 1945, Jackson had become the youngest Marine Corps Combat Artist in history.

Jackson then spent a winter at Pitchfork Ranch before relocating to New York in 1946. The story of Jackson’s life is sprawling and it’s obvious he had an affinity for Wyoming and the cowboy spirit.

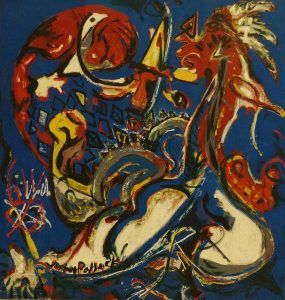

Adding to Jackson’s already unique set of accomplishments, he set out to meet Jackson Pollock after seeing his painting, The Moon-Woman Cuts the Circle.

Jackson had moved to Cody early in life, but Pollock was born in Cody. Despite this strange coincidence, the two first met in New York. They became friends and Jackson adopted Pollock’s abstract expressionist style.

The kind of abstract, avant-garde painting developed by abstract expressionism is now commonplace and well-known because of artists like Pollock and Jackson. The work is defined by automatic, spontaneous, and subconscious creation. The term “abstract expressionism” was first used in the United States by art critic Robert Coates in 1946.

Pollock would drip paint onto a canvas laid on the floor, a technique reminiscent of surrealist painters like André Masson and Max Ernst. For a time, Jackson painted like Pollock. It’s worth remembering that Jackson had been painting close-combat experiences for the Marine Corps during WWII.

“When he [Jackson] left the Ab Ex movement and went back to realism, he was not treated well by the Ab Ex proponent because,well, he left the movement,” Harris says.

As Harris explains, to say Jackson left “the movement” is not completely accurate, “even in some of his bronzes he would add in that Ab Ex color and patterning,” Harris explains.

In 1956, Life profiled Jackson in a piece called, “Painter Striving to Find Himself: Harry Jackson Turns to the Hard Way,” where the magazine described Jackson as an “American painter of surging talent and ambition.” By the time Jackson moved back to Wyoming in 1970, he had abandoned the art-for-art’s sake[1] credo of expressionism and returned to the realist mode of painting.

By 1980, Jackson had become one of the highest-paid American artists–he had finished a portrait of Bob Dylan in the mid-1960s, and he had been commissioned to create a sculpture of John Wayne after his death.

“He used to hang out with Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, the guy was amazing,” Harris says. “He [Jackson] did everything and he did it well.”

His bronze sculpture Sacajawea Modified II (2005) was featured in Cody’s prestigious Buffalo Bill Art Show and Sale. Jackson died in Sheridan on April 25th, 2011, at the age of 87.

The Harry Jackson Institute & Collection

The status and location of the Harry Jackson collection have faced uncertainty for years. NPR reported on the situation in 2013 with a piece titled, “Sun May Set on the Collected Works of a Western Icon.” That story addressed important questions about the safety, protection, and sustainability of Jackson’s body of work.

In 2018, the Jackson family gifted the corpus of its holdings to HJI, the institution dedicated to the preservation and interpretation of the art and archives of the Wyoming artist Harry Jackson.

At the time, it was the single largest gift of artwork in the history of the state of Wyoming. The collection is comprised of “5357 Artworks – 247 Bronze Sculptures, 2,540 Drawings and Sketches, 31 Monoprints, and Jackson’s 46 Sketchbooks (1,729 drawings, watercolors, monoprints, studies, and notes),” according to the Institute.

“The artist left behind an enormous estate spread over two continents and his heirs were charged with the complex task of simultaneously keeping the collection intact and liquidating assets,” HJI writes.

Moving forward to 2020-21, concerns have continued to be raised about the long-term care of this extensive collection.

An assessment made by the American Association of Museum’s Conservation and Preservation (CAP) in 2019 concluded that “storage conditions were far from ideal” recommending that “the collection be re-housed immediately.”

The Association also found that “paintings were hung on the floor or on temporary, inadequate, and built-in storage,” and papers were stored in “antiquated files and non-archival folders.”

The CAP Report has stressed the need to relocate the collection as “quickly as possible” since the current building has a “leaking roof” and “no fire suppression system” where “climate control is not maintained” and “security is minimal.”

Jackson’s collection is being housed in a building on Blackburn Street, but the structure is currently for sale. “Right now, we’re focused on finding another temporary home,” Harris says.

As of September 2022, HJI has secured grants to establish an Architectural Planning project, Harris explains. The Architectural Planning will follow several qualitative and quantitative steps, and the funding has been awarded by the Wyoming Arts Council. The Berggren Architects firm will be working with HJI on assessing institute needs.

Referring to some of the original portfolios containing Jackson’s work, “we have new storage, modern archival quality storage places for them and we want to take them out of the old storage, digitize them…we want to get them digitized so that we can set up online exhibits,” Harris says.

An upcoming meeting will be held to develop a plan and determine the needs of HJI and the collection, “it will tell us what kind of site we need, how big of a lot do we need, what kind of space do we need for gallery, what kind of space do we need to curate exhibits,” Harris says.

“We will have in hand a plan–we can go to Cody or Cheyenne or Dubois or Jackson and say, ‘okay, we would like to be in your community, this is what we need, how can you help us meet those needs,’” Harris states.

Harris emphasizes the importance of traveling exhibits in terms of increasing Jackson’s public exposure and in terms of monetary sustainability. HJI’s building needs are specific and somewhat time sensitive. Harris explains that they also need a workspace to repair damaged bronzes and sculptures, clean paintings, and so on.

Ultimately, towns and citizens in Wyoming will have to decide if they have the resources or the tenacity to create new, modern facilities for this world-class art collection.

“I was on the board for five or six years while Harry was still alive and sat in that very hall out there with him on many occasions, and I know Harry really wanted the collection to stay in Cody–he loved Cody,” Harris says.