Photographer Who Captured Iconic Gulf War Image Comes to Cody

Written by Caleb Nelson on November 3, 2022

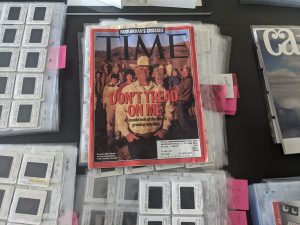

Kenneth Jarecke is an author, photojournalist, and war correspondent and he hardly needs an introduction. Jarecke has worked in more than 80 countries and has been featured in LIFE magazine, TIME magazine, National Geographic, and Sports Illustrated, among others.

He is a founding member of Contact Press Images and is notable for taking the famous photograph of a burnt Iraqi soldier that was published in The Observer, March 10, 1991. Currently, he resides on a sprawling ranch in southern Montana where he has raised his four children with his wife Souad.

On Tuesday November 8th, Mr. Jarecke is set to arrive in Cody, Wyoming where he will be hosting a photojournalism workshop at the Holiday Inn on Sheridan Avenue at 1:00 pm. Jarecke’s story is as unique as his iconic images.

New York to Montana

Jarecke first visited Montana for the Centennial Cattle Drive in 1989. This cattle drive was held to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Montana’s statehood in September of ‘89. It was called, “The Great Montana Centennial Cattle Drive,” and it included moving more than 2,800 cattle over 60 miles from Roundup to Billings over the course of six days.

“I called up my editor at LIFE magazine and I just said this is happening, I want to go,” Jarecke says.

At this point in Jarecke’s career, he could call one of his editors at LIFE or TIME magazine, pick a project, and be on a plane the next day.

In the winter of 1992, just before the Barcelona Olympics, a Sports Illustrated writer named Gary Smith was working on a story about Crow Basketball. Smith needed a photographer. Jarecke says of Smith, “He was their Hunter S. Thompson, right, he was their great writer.”

Jarecke spent three weeks “in the dead of winter” shooting basketball photographs for Smith, saying he, “loved it.” And by all accounts, he did love the work. Jarecke went on to cover the Olympics nine times during his career.

Not long after, Jarecke came back to Montana with his wife Souad. They were looking for land to purchase and a new home. The two had been living in a loft in Tribeca, a neighborhood in lower Manhattan.

“We had this ten-year plan to leave New York and move to Montana and start having a family – all that kind of stuff – because New York is just not the place to raise kids,” Jarecke explains.

During his trip to Montana, Jarecke’s agent called him to tell explain that his apartment had been broken into. The burglars had gained entry to the apartment “through the wall.” Two days later, Jarecke and his wife finalized their purchase of property in Montana.

At the time, Jarecke was still under contract with TIME magazine. He left New York in August.

“I was just fed up with New York,” Jarecke says. Oddly enough, when the criminals busted down the wall of his Tribeca loft, they accidentally knocked over a bookcase that then covered up “50 grand worth of camera gear,” which the thieves missed.

“When these guys busted through the wall, they knocked over the bookcase and it covered up all the gear…they left with nothing,” Jarecke says.

In September of 1992, Jarecke was living in Joliet Montana and Billings was the closest city with a decent airport. Billings was a relatively small town in ’92, but Jarecke says, “it had a good airport – so all I needed was an airport.”

Even though Jarecke was still traveling all around the world for work, he’d left New York for good. In Montana, Jarecke says he had “all the advantages of living in rural America.”

Jarecke started taking “little jobs” in the Rocky Mountain West, these were in addition to the larger projects he worked on for national publications. “I’d go from Montana to Idaho or Wyoming just because the editors back east would look at the map and see, ‘oh Ken’s in Billings, I guess he can run over to Cheyenne for the afternoon,’” Jarecke says with a laugh.

His bosses back in New York didn’t fully understand that traveling from Billings to Cheyenne is not the same as driving from New York to New Jersey. Still, Jarecke fell in love with the remoteness and the wildness of the West. He’s called it home ever since.

The Montana Freemen

On March 25, 1996, an armed, militant anti-government “Christian Patriot” group known as the “Montana Freemen” began a months-long standoff with agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The confrontation lasted 81 days and dominated international headlines.

“The FBI surrounded their compound for like a month,” Jarecke says. “I drove up there the first time out of curiosity.”

Jarecke’s curiosity led him to the center of classic American story: citizens pushing back against the authority of the federal government. In 1994, foreclosure proceedings were initiated against the land that contained Justus Township. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Freemen refused to be evicted from the land. Years of legal and financial trouble between the Freemen and the FBI persisted.

Eventually, the Freemen decided to block off a county road outside Jordan, Montana, and that’s when Jarecke says, “things got serious.” After deciding the road belonged to them, the Freemen erected a fence and a barricade, preventing traffic and travel.

The situation was tense, but day-to-day nothing was really happening. “There was nothing going on, right. There was a sign on the roadblock, and you’d never see anybody,” Jarecke says.

One afternoon, Jarecke was waiting at the Hell Creek Bar when he was approached by a photographer from Portland, Oregon who wanted to see the road the Freemen had occupied. It was 20 below and windy. Jarecke agreed and the two photographers drove twenty miles to the FBI checkpoint near a remote Post Office.

“So, we go through the roadblock and we’re driving and this poor photographer from Portland, he’s like, ‘so, where’s the next roadblock?’,” Jarecke says.

They were in the middle of Freemen territory in the dead of winter with no one around.

According to Jarecke, the Portland photographer began to get “visibly upset.” “All the sudden coming across the field was this white Suburban,” Jarecke says. This was the first time he’d seen any of the Freemen. Jarecke parked his vehicle about fifty yards away from the barricade, the Freeman pulled right up to it and stopped.

“There’s these two guys eyeballing us,” Jarecke adds. “I grab my cameras, put them around my neck, and I turned to the guy and said, ‘now, if they shoot me, you just get in this truck and drive back – you just go’,” Jarecke says.

Jarecke ventured within ten yards of the Freemen before they yelled, “that’s far enough.” Two men exited the white Suburban armed with rifles. Jarecke took pictures of the Freemen and their guns at the barricade as they stared at him.

By the time Jarecke returned to his truck, the Portland photographer was lying on the floor in the back seat hiding, expecting that Jarecke had been shot and killed. “He was a mess at that point,” Jarecke says with a chuckle.

This photographer from Portland, who hid in the backseat of the truck while Jarecke approached the two Freeman in a remote part of Montana in the middle of winter, won a photojournalism award for a sequence of pictures he took of Jarecke from the truck before dropping back down and hiding out of sight.

“He’d gone back to his newspaper and told this whole story about how, you know, he came across this scene and, like, didn’t even mention my name,” Jarecke explains, still slightly annoyed.

What Makes a Photojournalist?

“There are two traits, you’ve got to be really curious, and you have to have empathy. If you’re not curious, you never get out of the truck – right?” Jarecke says, explaining the temperament of a good photojournalist.

Most photojournalists, Jarecke says, wouldn’t drive forty miles in the thick of a cold and icy winter in Montana just to “see what’s happening.”

“It’s easier to stay and eat a cheeseburger at the bar,” Jarecke adds. For Jarecke, curiosity is what fuels the best journalists.

“To make images that are lasting, and have impact, and that connect with the viewer, you have to have empathy with the subject,” Jarecke explains.

The danger of not looking at the world from the perspective of the person or thing being photographed, for Jarecke, is that images of this kind fail to properly tell the real story. “Somehow you have to put the viewer through your work into the lives of other people – it should be impossible, it shouldn’t work,” Jarecke states.

Empathy, curiosity, and the “eyes of an artist,” make still image photography a unique thing in the world, Jarecke says. “I don’t think there’s another medium that can compete with it.”

“We just talked a few minutes ago about Napalm girl, right, a child and her brother running down a road in South Vietnam naked on fire. It’s a still image and it moves you today if you see it,” Jarecke says.

Nick Ut’s photo of Kim Phuc (referred to informally as ‘Napalm girl’) changed the Vietnam war, Jarecke explains. The New York Times ultimately ran the photo but was hesitant to do so. The American military complained about Ut’s photo. Richard Nixon thought the photograph had been staged. Of course, the image had not been staged, and it went on to win the Pulitzer Prize after becoming one of the most iconic images of the 20th century.

Like Ut, Jarecke also captured an internationally famous wartime photograph during his career. In 2014, The Atlantic ran a story by Torie Rose DeGhett called, “The War Photo No One Would Publish.” DeGhett writes, “When Kenneth Jarecke photographed an Iraqi man burned alive, he thought it would change the way Americans saw the Gulf War. But the media wouldn’t run the picture.”

Jarecke’s photo of the Iraqi soldier, during Desert Storm, who died attempting to pull himself out of his vehicle while being engulfed in flames and incinerated should have been published in America—it wasn’t. Instead, the photograph was first published in France and in the U.K.

DeGhett compares Jarecke’s photograph to Ut’s “Napalm girl.” Although, as DeGhett’s article aptly points out, not all gruesome images are profound, insightful, or helpful. However, in the case of Jarecke’s charred Iraqi soldier photo, “the hypnotizing and awful photograph ran against the popular myth of the Gulf War as a ‘video-game war’—a conflict made humane through precision bombing and night-vision equipment,” DeGhett writes.

In other words, Jarecke’s photo mattered—it shouldn’t have been ignored.

There are countless hours of video footage from Vietnam and the Gulf War, but Jarecke says, “the still images are what we remember.”

The Curious Society

Jarecke’s career is vast, complex, and accomplished, it cannot be summarized quickly or succinctly. Every cover and each photo in Jarecke’s archives have a story to tell.

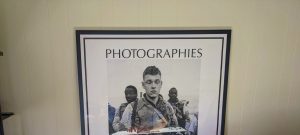

These days, Jarecke is running, managing, and printing perhaps the single most ambitious documentary photography publication in the United States, The Curious Society. This publication was started to educate and support photographers working in the photojournalist tradition.

“What you’re doing as a documentary photographer, as a photojournalist, is bringing order to chaos,” Jarecke says.

In the moment, opportunities to turn the chaos of reality into quality images come and go—quickly. When there’s tension, when bullets start flying and adrenaline starts flowing, that’s when Jarecke says photographers have to be “really schooled in their craft.”

For Jarecke, seasoned photojournalists don’t get tunnel vision. They don’t get panicky—they start looking for compositions. Time slows down.

“It’s kind of scary when you think about it,” Jarecke says. “It’s not a natural response to suppress the fight or flight instinct.”

The difference between the amateur photographer and the professional, Jarecke says, is that they’re not just “motoring through the scene and then trying to pick something out later, it’s a deliberate act. It has intention.”

The values of The Curious Society, as a publication, mirror Jarecke’s values regarding photojournalism, forged through decades of trial and error, patience and practice, risk and reward. The book-length first issue of The Curious Society is meant to be the “ideal place to share the best photojournalism being produced today.”

It’s clear that Jarecke cares about images that will last and endure, a tough thing to come by in the age of the iPhone and social media.

“If you don’t have empathy, you’re making images that have no reason to exist,” Jarecke says.